A Bottoms-up Guide to WASM with Rust - Part 1

Recently, I've been working with WebAssembly using Rust. There is a fantastic ecosystem in Rust for

running code in the browser using tools like wasm-bindgen and web-sys to provide abstractions

over the FFI and bindings for JavaScript APIs. While these tools are great and you should use them,

it's also critically important to understand how the WASM/JS interface works and where the boundaries and

bottlenecks are in order to design performant and correct applications.

With that goal in mind, today we're setting out on a multi-part guide to build up this understanding by building some

simple WASM projects from the bottom up. In part 1 (this post!) we'll deal with doing things the hard way:

we'll be writing pure Rust and JS without any helper libraries, instead passing the data we need back and forth manually.

In the next part, we'll layer wasm-bindgen and web-sys on to what we've built to solve some of the problems we identify in this exercise.

Quick disclaimer: Part 1 of this guide presents interfacing WebAssembly and JavaScript in a way that you probably don't want to do for any serious projects.

If you're just looking for a quick-start with WebAssembly and Rust, check back in a few weeks for part two, or check out the awesome Rust and WebAssembly book

WebAssembly and JavaScript

Before we get on to hacking on some code, we'll need to take a quick look at WebAssembly and JavaScript to get the lay of the land. I promise it will go quick.

I have good news for some, bad news for other: WebAssembly does not entirely replace JavaScript, nor was it designed with that goal in mind. Instead, it should be thought of as a low-level counterpart to higher-level JavaScript. This also means that interoperating between the two has a few... extra considerations.

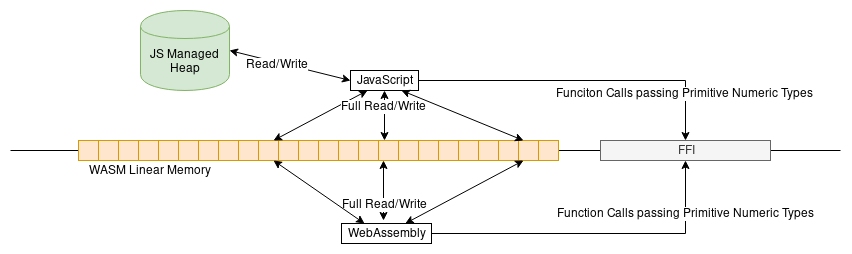

When you load your compiled WASM in a browser, it gets loaded as an ES2015 module and, as such, exports a number of functions that JS can call into. Likewise, it can import JS functions and call them directly. However, the two sides don't get access to all the same memory. JS runs as normal with a fully managed heap, and WASM gets a linear array of bytes to do with as it sees fit. WASM has no visibility into the JS heap, and no access to native objects (at least the time of this writing; this proposal attempts to address this limitation). Furthermore, you're limited to being able to pass only primitive numerical types to functions that WASM exports and to JS functions that WASM imports.

From the JavaScript side, however, you have full read-write access to WASM's linear array of memory. This means you can serialize and write complex objects into the memory to be picked up by WASM, or you can read out large objects after they've been worked on by your WASM module. Coordinating this effort, however, is up to you.

In practice, this boundary will influence most design decisions that need to be made when constructing an application. Copying large objects into and out of the WASM linear memory and serializing/deserializing them is expensive; to avoid incurring this overhead, you should try as best you can to minimize copying data across the boundary. Instead, it's generally preferable to have larger, longer-lived objects live in the WASM side and return a smaller, easily copied result when computations are complete.

Let's code!

All examples presented here can be found in the git repo for this post. The doc comments in the presented examples give paths to the file within this repo.

Project Setup

Now that that's out of the way, let's move on to building something! In this post, we'll be working through a fairly standard Hello World. We should now set up the project. Open up your terminal and create a new library crate wherever you see fit:

$ cargo new my-wasm-project

We need to let the rust compiler know we intend our project to be used as a library that interfaces with an external FFI and that

it should not include rust-specific stuff in the final code.

To do so, add this to your new crate's Cargo.toml:

[lib] crate-type = ["cdylib", "rlib"]

We need to be able to serve the built webassembly module, an HTML page, and the JavaScript that runs everything,

so create a /public directory within the project and create an index.html page and a load_wasm.js script.

Your project should look like the following:

my-wasm-project/

src/

lib.rs

public/

index.html

load_wasm.js

Cargo.toml

At this point, you should figure out a way to serve the contents of the public/ directory that works for you. If you have python installed

on your system, you can serve everything in public/ by running this handy one-liner from within the directory:

$ python -m http.server 8080

Once the http.server module loads, you can get to index.html by opening http://localhost:8080/ in your browser.

A Naive (and broken) Hello World

We'll be building build the quintessential browser Hello World: our project will display an alert to the user when the page loads. Later, we'll enable JavaScript to pass a name to our WebAssembly module, and WebAssembly will greet the user by name.

To accomplish this, we'll have to do the following:

- Let the Rust compiler know we want to import the

alertfunction from JS. - Export a function from Rust that calls the

alertfunction with our greeting. - Load the module from JS and call the exported function.

To start, open up src/lib.rs and add this (naive) code:

//! part1-broken-alert/src/lib.rs /// Pull in the alert function. extern { /// Alert from JS. fn alert(s: *const u8); } /// Greet the user with an alert message. #[no_mangle] pub extern fn greet() { let message = String::from("hullo werld"); // call the alert function unsafe { alert(message.as_ptr()) }; }

Let's look at what this is doing:

- Let the compiler know we want to import a function called

alertthat takes a pointer-to-u8. - Define our

greetfunction that JS will call. Note that for it to be exported properly from our module, we need to decare itexternand annotate it with#[no_mangle]so the compiler uses the correct calling convention. - Call

alert. We're calling anexternfunction, so this is an unsafe operation.

This covers items 1 and 2 on our list, now to wire up the JavaScript side. Open up public/load_wasm.js and drop in this code:

// part1-broken-alert/public/load_wasm.js (function() { // Create an object to pass reference to imported functions to // our wasm module. var import_obj = { env: { alert: alert, }, }; // Load the wasm module. fetch('my_wasm_project.wasm').then(response => response.arrayBuffer() ).then(bytes => // Instantiate the wasm module WebAssembly.instantiate(bytes, import_obj) ).then(results => { let wasm = results.instance.exports; // call greet! wasm.greet(); }); })();

The javascript code is fairly straight-forward: fetch the module, instantiate it, and call the exported function. Easy!

Note that we're fetching the wasm module and using the WebAssembly API's

instantiatefunction instead of the much more convenientinstantiateStreamingfunction.instantiateStreamingenforces that the module you fetch has a mime type ofapplication/wasm, however many webservers incorrectly interperet wasm modules asapplication/octet-stream. Until web servers catch up, the presented approach may be more reliable.

Finally, let's add some content to our index.html page:

<!DOCTYPE html> <!-- part1-broken-alert/public/index.html --> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="UTF-8"> <title>Testing!!!</title> </head> <body> <script type="text/javascript" src="load_wasm.js" ></script> </body> </html>

Let's run it! We need to build the project, copy the module into our public/ folder, and serve it:

$ cargo build --target=wasm32-unknown-unknown $ cp target/wasm32-unknown-unknown/debug/my_wasm_project.wasm public/ $ cd public $ python -m http.server 8080

Eagle-eyed readers will have noticed that there is a problem with the above code, and that it won't do what we're expecting. If you haven't spotted it yet, take a minute to read through and see if you can figure it out!

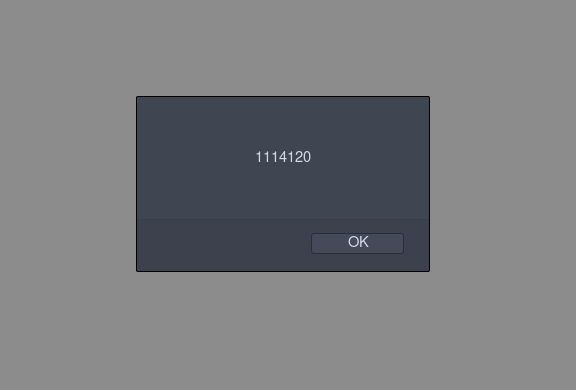

When I run the code on my system, I get this:

Huh. Doesn't really look right, does it? Recall a few things about interfacing with WASM modules:

- We can only pass primitive numeric types as arguments or return values

- Objects allocated by WASM are referenced by pointers that are (effectively) indexes into WASM's linear memory

It stands to reason here that we've just alerted the user with the index of the string in WASM's memory, and not the string itself!

A Working Hello World

In order for JS to get the string, we'll have to change a few steps of our program. Here's the revised version:

- From the WASM side, export a

greetfunction that will create a string and pass a pointer to an imported JS function. - From the JS side, extract the string from the WASM memory referenced by the returned pointer.

- From the JS side, call

alertwith the extrated string

The new Rust code becomes:

//! part1-working-alert/src/lib.rs extern { /// Import a function that accepts a pointer to the string /// _and_ its length. fn alert(ptr: *const u8, len: usize); } /// Greet function. #[no_mangle] pub extern fn greet() { let message = String::from("hello werld"); // Pass a pointer to the string as well as the length in bytes. unsafe { alert(message.as_ptr(), message.len()) }; }

Nice! This didn't have to change much. The only extra information the JS side needs is the length of the string in bytes (we're dealing with unicode strings, so the number of bytes does not correspond to the number of printable characters)

Things do get a bit more complicated on the JS side, however:

// part1-working-alert/public/load_wasm.js (function() { var wasm; // Takes a pointer to a string and length, // decodes the string and calls alert(str). function __alert(ptr, len) { // Pull the raw data out of wasm memory. let mem = new Uint8Array(wasm.memory.buffer); let slice = mem.subarray(ptr, ptr + len); // Decode the string. let decoder = new TextDecoder('utf-8'); let str = decoder.decode(slice); // Call alert! alert(str); } // import object to pass to our wasm module. var import_obj = { env: { alert: __alert, }, }; // fetch the wasm module, instantiate it, and // call our greet function. fetch('part1_working_alert.wasm').then(response => response.arrayBuffer() ).then(bytes => WebAssembly.instantiate(bytes, import_obj) ).then(results => { wasm = results.instance.exports; wasm.greet(); }); })();

To handle retrieving the data from WASM's memory, we've added a shim function called __alert between

the WASM module and the alert call. Its job is to fetch and decode the UTF-8 string from the WASM module's

memory, and call alert with it.

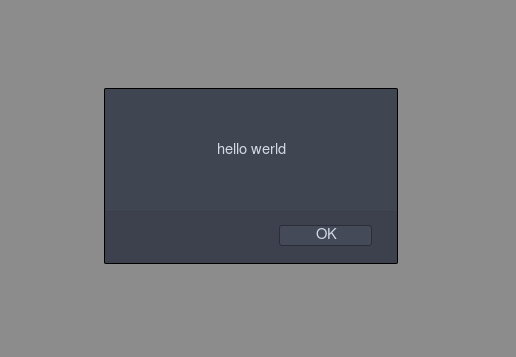

Running the updated example should give you this:

Huzzah! It works!

Hopefully this is starting to give you a good idea of what passing data and calling functions across the wasm/js boundary looks like. Next, we'll follow this example through the next logical iteration: greeting someone by name.

To WASM and Back Again

We want to greet someone by name, and we want that name to be passed to our WASM module from JavaScript. Recall that JavaScript has full read-write access to the WASM memory. With that in mind, the task ahead of us should look something like this:

- From Javascript, write a string to some place in the WASM memory and note the index.

- From Javascript, pass the index and length to the WASM module.

- From WASM, construct a string from the passed-in pointer and length.

- From WASM, construct a string

Hello, {name}and callalertas before.

Seems simple, right? But look at the first item on the list. The obvious question is: where are we going to write the string to? How does the JavaScript side know what memory is unused, and how can we ensure that the memory we use gets cleaned up properly?

To do this properly, we need to expose some mechanism from our WASM module to allow JavaScript to allocate memory. This makes the WASM side aware of the allocated memory and allows us to manage it properly.

Let's do that! Here's the function, and the changes to greet:

//! part1-custom-alert/src/lib.rs use std::alloc::Layout; use std::alloc::alloc; /// Allocate memory for javascript to use. #[no_mangle] pub extern fn do_alloc(num_bytes: usize) -> *const u8 { // Create a layout for the memory. let layout = Layout::from_size_align(num_bytes, std::mem::align_of::<u8>()) .expect("couldn't create a layout"); // Do the alloc. let ptr = unsafe { alloc(layout) }; // Return the pointer. ptr } /// Export a `greet` function from Rust to JavaScript that takes /// a string and alerts "Hello {name}!". #[no_mangle] pub extern fn greet(name_ptr: *mut u8, len: u8) { // Create a string around the raw name passed from javascript. // Note that from_raw_parts takes ownership, ensuring the string will get dropped. let name = unsafe { String::from_raw_parts(name_ptr, len as usize, len as usize) }; // Create our message. let message = format!("Hello {}!", name); //Call alert. unsafe { alert(message.as_ptr(), message.len()); } // The strings gets dropped here, and the memory cleaned up. }

We're allocating memory using

allocbecause, at the time of writing, theAlloctrait has not yet been stabilized.

The do_alloc function will allocate a given number of bytes in WASM's memory and return the index

to the caller. We've also modified greet to accept a pointer and length to use to create a String, format the message,

and call alert as before.

We can wire this up with JavaScript like so:

// part1-custom-alert/public/load_wasm.js // ... // Passes the string to our wasm module and // calls the exported greet function. function call_greet(name) { // Encode the string as bytes. let encoder = new TextEncoder('utf-8') let encoded = encoder.encode(name); // Allocate some memory for our wasm module and set // it to the encoded string. let ptr = wasm.do_alloc(encoded.length); let mem = new Uint8Array(wasm.memory.buffer, ptr); mem.set(encoded); // Call greet with the pointer and length. wasm.greet(ptr, encoded.length); } // ... // replace wasm.greet() with: call_greet("nerd"); // ...

Runing the new code, we get:

It works!

In Conclusion

We've seen how we can work across the WASM/JavaScript boundary to get things done, but there are some obvious issues with this approach:

- We have to manage a lot memory ourselves.

- There's unsafe code all over the place.

- There's a lot of error-prone boilerplate dedicated to moving values across the boundary.

Thankfully, this is where the excellent wasm-bindgen comes in to help out. wasm-bindgen will

generate code at compile time for us that takes care of everything we did manually here, and allows

us to write Rust without comprimising the abstractions it gives us over memory management and lifetimes.

In the next installment of this guide, we'll layer in wasm-bindgen and web-sys, which serves to give

an abstraction over dealing with native JavaScript objects. It'll be a hoot, so check back soon!

If you're hungry for a more complex example of what we've been through today, the example repository for this post contains an extra project that computes a julia set and draws it directly from WASM's memory to an HTML canvas. Take a look if you're interested!

Thanks for reading!